In 2013, the far-right politician Marian Kotleba won a shock victory in regional elections. Four years later, he was voted out in a landslide. But now he’s running for president.

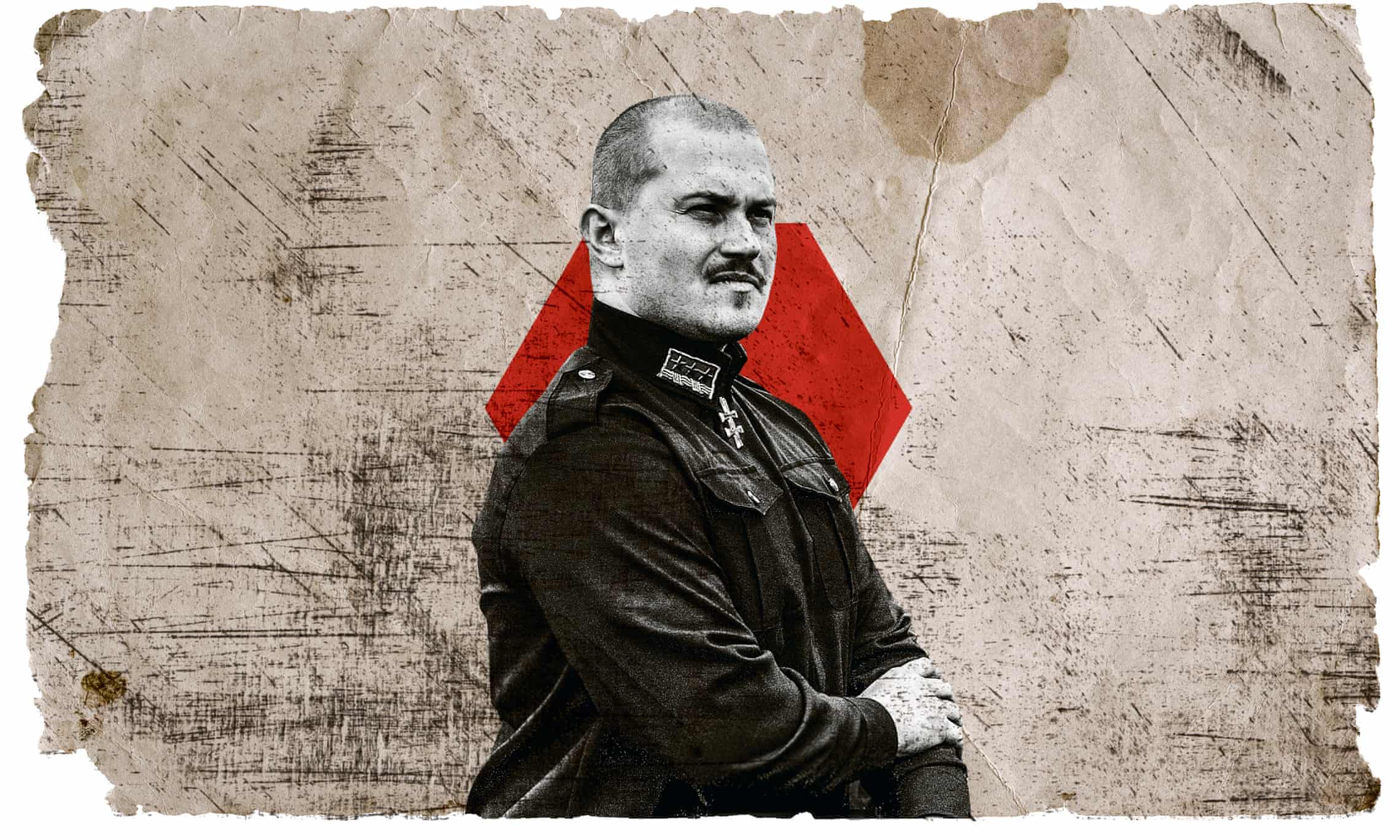

In December 2013, Marian Kotleba, a former secondary school teacher who had become Slovakia’s most notorious political extremist, arrived to begin work at his new office – the governor’s mansion in Banská Bystrica, the country’s sixth-largest city. Kotleba venerated Slovakia’s wartime Nazi puppet state, and liked to dress up in the uniforms of its shock troops, who had helped to round up thousands of Jews during the Holocaust. Now, in the biggest electoral shock anyone could remember in the two decades since Slovakia’s independence, the people of Banská Bystrica and the surrounding region had voted for the 37-year-old Kotleba to be their governor. The four-storey mansion, with its vaulted ceilings and gilded pillars, would be his workplace for the next four years.

Banská Bystrica is a tranquil kind of place, with a genteel Mitteleuropa charm: the centre has pavement cafes, neat rows of burgher houses and a number of handsome baroque churches. At eight minutes to every hour, a clock in the central square plays a dainty jewellery-box jingle. And now, it had the dubious distinction of being the first place in modern Europe to have elected a person widely regarded as a neo-fascist to a major office.

For the next four years, heavy-set men in the green shirts of Kotleba’s Our Slovakia party guarded the door of the administration building; they worked out in a gym that was constructed for them in the basement of the governor’s office. Journalists, for the most part, were forbidden to enter. Kotleba branded the mainstream media liars, and said he would communicate directly with the people. An industrial printing press, brought into the building early in his term, pumped out regular pamphlets called Our Slovakia, which were sent across the region, and later, the country.

The colourful, four-page leaflets were packed with the tropes that had defined Kotleba’s campaign: decent Slovaks were being exploited and terrorised by corrupt politicians, “Gypsy criminals” and shadowy international forces. Articles railed against promiscuity, abortion and homosexuality, all of which threatened the traditional family and the Slovak nation. Often, there was a personal appeal from Kotleba not to believe the “tendentious opinions” about him in the media. Tall, stocky and balding, and always wearing a neatly trimmed moustache, Kotleba looked equal parts supply teacher and gang leader. He had a purposeful strut and a boxer’s habit of shifting his weight from one foot to the other. At meetings and rallies, he spoke in a hectoring, insistent tone about the urgency of his tasks.

In many of the smaller settlements there were simply not enough jobs, and the most talented people got out as soon as they could. There was a vague resentment at being seen as second-class citizens inside the European Union, and a more acute feeling that the Slovak political class was isolated from the masses and only interested in lining its pockets. Soon enough, the same issues would fuel the rise of rightwing populism across the region. Within a few years, after migration and nationalism had taken over the political agenda, much of Europe would also be grappling with the far-right’s success at the ballot box. But back in 2013, nobody was expecting a neo-Nazi to win an election. How was it possible that 55% of voters had backed someone this extreme?

Three years later, Kotleba pulled off another electoral shock, using his platform as governor to take his far-right party into parliament after a vigorous campaign in small towns across the country. Our Slovakia won 14 out of 150 seats in the Slovak legislature. In March, he will run for president.

In Slovakia, regional governors are responsible for the unglamorous nitty-gritty of local administration: bus timetables, road maintenance and some education and healthcare. The country’s population of about 5.5 million is divided into eight regions; in the west, the capital, Bratislava, brushes against the Austrian border and is just a short hop from Vienna. In the east, the country stretches to the Ukrainian border. Banská Bystrica, the largest region by area, is right in the middle, a three-hour train ride from the capital. The city of Banská Bystrica itself is something of an intellectual hub, with four theatres and a well-regarded university, but the surrounding region is regarded as a hinterland of dessicated industrial plants and unprofitable agricultural concerns. Most of the small towns, linked by winding and poorly paved roads, were the sort of places whose names caused metropolitan Slovaks to raise their eyebrows in consternation.

During his campaign, Kotleba had promised to stand up for the “decent people”. They had been getting a raw deal, he said, exploited by both the “political mafia” in charge of the country, and “Gypsy parasites”. Many Slovak politicians used inflammatory language about the country’s Roma community, but Kotleba took it a step further. Members of his party, in their distinctive green shirts, even prowled trains on special vigilante patrols designed to “prevent Gypsy criminality”.

In land and property disputes that broke out with Roma families, Kotleba frequently sent party members to intimidate the Roma or force them off land they were deemed to be occupying. The tales of such heroic rescue operations coming to the aid of “decent people” were written up in lurid detail in the pamphlets cranked out by the printing press. Instead of being the crazed ravings of a fringe lunatic, they now came imprinted with the approval of a man serving in high office.

Kotleba rebuffed my attempts to talk with him, saying he did not trust western journalists, so, instead, I met Milan Uhrík, who was Kotleba’s deputy in Banská Bystrica and is now an MP from his party. We drank coffee in a shopping mall outside his home town of Nitra, an hour’s drive away from Banská Bystrica. Regarded as the polished face of Kotleba’s party, Uhrík had a couple of days’ worth of light stubble and wore a checked shirt. He spoke to me softly in fluent English, and although he was friendly enough, within seven minutes of us sitting down, he was on the defensive, insisting unprompted that he had no problems with “the Jews”. He repeatedly denied Kotleba or the party was racist or fascist, batting away criticism with wide-eyed mock-surprise and the predictable retort that the real victims of discrimination were white Slovaks.

Uhrík ran over what he saw as the achievements of Kotleba’s time in office, which he lamented were fairly miserly only because the central government had blocked them from doing more. I asked him what he was most proud of, and he buried himself in his phone, looking for the right English translation. “Ah, pickaxes, that’s the word,” he said with a boyish grin. “Pickaxes and shovels – that was our programme.” The policy in question hit on two of Kotleba’s favourite themes in one: Roma and roads. It involved long-term unemployed people being put to manual labour on the roads, using the simplest of tools. It employed around 90 people, many of them Roma. “They couldn’t work with computers, or do some business, they were simplest people on the labour market, but they have to do something because when they sit at home and do nothing they just start drinking, stealing and doing some criminal stuff,” he said. Kotleba’s programme was widely criticised for being both demeaning and pointlessly inefficient. It was soon shut down by the regional parliament – in Uhrík’s mind, because they were alarmed by its success.

Uhrík was on his way to Banská Bystrica to plot strategy with Kotleba, and gave me a lift in his roomy black Mercedes, bought with money from his successful pre-politics IT career, he said. We drove past a shopping centre where the Kotleba green-shirts were doing unsolicited, informal security patrols, a new offshoot of the train-patrol programme. “The Gypsy gang was threatening the managers who were selling clothes in shops,” he said, gesturing at the mall as we sped past. “The police did nothing. When our members come, the Gypsies have more respect for our members than for the police. The police cannot do anything because they’re too scared to be marked as racist.”

Uhrík spent a lot of time talking about “Gypsies”, mostly involving him explaining how the party was not racist, in terms that sounded incredibly racist. After an hour’s drive through a hilly landscape of golden fields and trees that were just starting to turn with the onset of autumn, he dropped me off in Banská Bystrica. He bade me farewell, and promised to intercede personally on my behalf with his boss, although he looked doubtful. A few days later, the final rebuttal came by email. Kotleba would wait to see what kind of article I wrote, before deciding whether to speak to me in the future.

Slovakia’s short history as an independent state began in 1993, when Czechoslovakia split in two. Four years previously, crowds across the old country had surged into city squares and demanded the end of the Moscow-backed communist regime, in a series of demonstrations that became known as the Velvet Revolution. The old order melted away without violence, and enthusiasm for the new politics was high: in the 1990 elections, the first after the Velvet Revolution, the turnout was over 96%. The 1993 divorce with the Czechs was also peaceful – but ahead lay a difficult transition, involving the speedy creation of a new economy and new political institutions, as well as the search for new national identities after four decades of communism. The country joined the EU in 2004.

These momentous changes formed the backdrop to the younger years of Marian Kotleba, who was born in 1977 in Sásová, a drab suburb of Banská Bystrica. But from Sásová’s collection of nine-storey apartment blocks filled with boxy, functional apartments, the political shifts would have felt distant. There wasn’t much to do, and subcultures flourished among the bored youth. At least one of Marian’s older brothers was involved with a clique of far-right skinheads, but Marian was a quiet, shy kid. He kept his head down and didn’t say much, according to the recollections of his contemporaries.

After completing an economics degree at the local university, followed by a masters, he got a job at a local secondary school teaching IT. One of his former students, Michal Dzurko, told me Kotleba was a competent but strict teacher, who would sometimes play videogames with his favoured students after classes. During these sessions of a game called Unreal Tournament, Dzurko recalls Kotleba taking delight in introducing characters named after other teachers at the school. “Yeah bitch, take that,” he would yell, as he shot his computerised colleagues.

One day in 2005, Kotleba’s students realised their IT teacher had a secret life, when they saw him on the news, leading a gang of neo-fascists parading through the nearby town of Zvolen holding flaming torches. There on television was Kotleba’s boyish face, adorned with a thin moustache, a gap shaved in the middle to create the effect of a half-opened drawbridge. He wore a black peaked cap and a black shirt, with an armband featuring the double cross of the wartime Slovak state, a close Nazi ally. The uniform was almost identical to those of the Hlinka Guard, the fascist state’s shock troops.

Now that the quiet teacher’s alter-ego had been outed, Kotleba brought his ragtag band of extremists into a political party called Slovak Unity, of which he was leader. It was not a success: in 2006 elections it got just 0.16% of the vote. Dzurko, Kotleba’s former student, had fallen in with an extreme-right crowd as he progressed through school. At home, he spent long hours reading conspiracy websites about Jewish cabals and the oppression of the Slovak people and on Friday nights would go out and look for fights. And yet, even for people like Dzurko, Kotleba was seen as a bit of a joke. After the 2006 elections, Dzurko and friends saw Kotleba in the street and began shouting “Zero! Point! Sixteen! Percent!” at him.

After being crushed at the polls, the party was liquidated by the courts in 2006 for its overtly anti-democratic nature. Kotleba took a brief break from politics, opening a shop in Banská Bystrica called “KKK – English fashion”. The three Ks were meant to represent the three Kotlebas, but the Ku Klux Klan reference was fairly obvious, especially given the clothing on sale – T-shirts and hoodies with far-right emblems and insignia. Kotleba and his followers regularly dressed in Hlinka Guard uniforms (making minor alterations, as the actual uniforms were illegal). “We are Slovaks, not Jews, and that is why we are not interested in the Jewish issue,” he said in 2009, when asked about the wartime deportations of the Jews from Slovakia by the very unit in whose uniform he was dressed.

Soon, he was back in politics with a new outfit called People’s Party Our Slovakia. This time, Kotleba was much more careful when it came to the party programme, and obviously neo-Nazi or anti-democratic policies were excised. It didn’t help much, though. At elections in 2010 and 2012, the party got less than 2% of votes.

It was clear that full-on neo-Nazi ideology was never going to garner more than fringe support, but Kotleba saw that by softening the message a bit, there was a much larger electorate potentially available. The black uniforms were swapped for green T-shirts bearing the party logo. Sometimes he even wore a shirt and jacket. He stopped talking about the Jews and started talking more about the Roma. Antisemitism wasn’t much of a vote-winner in Slovakia, but promising recriminations against the country’s Roma community would be much more effective. Locked out of education and the workplace, many of Slovakia’s 400,000 Roma were trapped in a spiral of disenfranchisement, poverty and sometimes crime. “After decades of marginalisation you can’t just change it in a few years,” Michal Vašecka, a Slovak sociologist, told me. “And if anyone tries to do something openly to help the Roma, it’s political suicide.” Indeed, any time even basic employment or housing rights programmes were launched, Kotleba and others would complain about the Roma getting special treatment. Kotleba didn’t call them Roma, but used the semi-pejorative “cigani” (“Gypsies”), and he promised to get tough with them.

Kotleba thus relaunched himself as a straight-talking, no-nonsense guy, who would stand up for decent people – slušní ľudia. This became his refrain. He repeated it, again and again, in his campaign speeches and literature. Slušní ľudia would be protected from economic corruption, slušní ľudia would be shielded against moral decay, slušní ľudia would no longer be terrorised by “Gypsy criminality”. The man who had only recently marched in the uniforms of Holocaust perpetrators was now portraying himself as the paragon of decency.

The Slovak political scene in 2013 was dominated by the Smer (“Direction”) party, headed by prime minister Robert Fico. The party had been tainted with a number of corruption scandals, cronyism and links to shady oligarchs. In many ways, the supposedly centre-left Smer was similar to Viktor Orbán’s far-right Fidesz, in neighbouring Hungary. “Neither Fidesz nor Smer have a clear ideological direction, and both Orbán and Fico are very adaptive politicians,” said Zsuzsanna Szelényi, a former Hungarian MP who is now a visiting fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. The Hungarian electoral system, together with Orbán’s ruthlessness, allowed him to take a much firmer grip of his country than his Slovak counterpart: Smer dominated the electoral scene, but often had to govern in coalition.

The 2013 election for Banská Bystrica governor was meant to be a formality for Vladimír Maňka, a local Smer functionary. He had been in the job for four years, and was combining his post as regional governor with a job as an MEP. With a neatly trimmed shades-of-grey moustache, receding grey hair and spectacles, Maňka looked every inch the classic Smer man. He was a competent technocrat, born in the region, and he worked Stakhanovite hours – but with the double workload he was only in Banská Bystrica two-and-a-half days per week, flying in from Brussels or Strasbourg. He was not personally accused of corruption scandals but was tarnished by association with Smer. During the campaign, a mischievous series of billboard advertisements appeared, of unknown provenance, featuring a photograph of Maňka and thanking voters for his enormous salary.

Among Banská Bystrica’s small group of far-right skinheads, there was an excitement about the newly ascendant Kotleba, but at the same time he was cultivating a new type of voter. The area around Banská Bystrica was once dotted with silver and tin mines, which had brought prosperity for centuries. But the treasure had long been exhausted, and with the collapse of the socialist agricultural system, the small towns and villages were in a sorry state. Many of those who had opportunities to do so departed for Bratislava, Austria or Britain: out of a regional population of 650,000, the local government estimated that roughly 50,000 people had left in the decade since EU accession. Many of those who remained in the provinces felt isolated from the regional government in Banská Bystrica, let alone from Bratislava or Brussels. “There’s nothing here; all the clever people have gone,” several different people muttered to me wistfully, during my travels around the region.

Daniel Vražda, a burly and tenacious local reporter who has lived his whole life in Banská Bystrica, had first noticed Kotleba in 2005, when he caught the public eye with his torchlit marches, but initially dismissed him as a nobody, as most people did. Now, though, Vražda was travelling around the region watching Kotleba campaign, and could see with his own eyes how the revamped politician was connecting with the people he met. Nobody had ever bothered to campaign in the small towns before, but Kotleba went to these places, where it was hardly less surprising to see a real politician appear in the flesh than it would have been to see a herd of elephants stroll into town.

He held small gatherings, listened to people’s grievances, and told them that everyone was stealing from them, the decent people, the slušní ľudia. Vražda looked on, and thought that if he didn’t know what Kotleba really stood for, he too might have been persuaded by a lot of the messaging. Kotleba promised new and better local roads, a fairer deal for all, and action against the Roma. The specifics were left vague. “He told everyone he would make order with the Gypsies, but he never explained how,” Vrazda told me. “So, one person could imagine a job-creation programme, while another person could imagine baseball bats.”

Maňka, on the other hand, used his few campaign appearances to boast about the apparent economic prosperity he had brought. “Maňka kept talking about €160m (£140m) he had attracted to the region, thinking people would thank him for this,” said Vražda. “But they’re earning €400 a month, and these numbers mean nothing to them. The numbers are probably true, but if ordinary people tried to find the money, they wouldn’t. And then Marian Kotleba came along and said, ‘I’ve found the money. It’s in the pockets of Vladimír Maňka.’”

Despite all this, on election night things went more or less as planned for Maňka. He got a fraction less than half the vote, meaning there would be a run-off. Kotleba was the surprise runner-up, but he was way behind, on 21%. Conventional wisdom dictates that if an extremist candidate sneaks into the final round of voting, the moderate will see them off, a hypothesis borne out by two generations of Le Pens in France, among many others. In parts of the Slovak media there was alarm that a neo-Nazi had made it to a run-off, but everyone expected the second vote to be a formality. “I have absolutely no doubt that Mr Maňka is going to win the second round without a single problem,” prime minister Robert Fico said in a television interview. He added, with a laugh: “Even a sack of potatoes would beat Marian Kotleba.”

And then the unthinkable happened. In the first round, Maňka had been just 600 votes short of an outright majority; this time he was trounced, with Kotleba receiving 55% of the vote. The turnout was still a miserly 25%, but it seemed that while many Maňka voters had not bothered to turn up to vote for a second time, Kotleba had energised a different set of new voters with his promises to stand up for the “decent people”.

When I met Maňka recently to discuss the 2013 vote, it was clear the subject is still a raw one. He remains an MEP, but mention his name even now in Slovak political circles and someone will say “sack of potatoes” with a snigger. Maňka arrived at our breakfast meeting with a bag of props, including literature filled with graphs and pie charts showing how successful his time in office had been. He placed on the table a glass award he had won in 2013 for running the most transparent region in Slovakia. The US ambassador, with whom he used to play tennis, had personally awarded it to him, he said.

Maňka didn’t seem to think actually winning the approval of voters had even been part of his duties. “I didn’t campaign, I was busy working and solving all the problems,” he told me, about the time between the first and second rounds of voting. “We had solved everything, the region was healthy, I was very happy.” Five years later, he still looked genuinely confused by the result.

A few weeks after the vote, Kotleba was confirmed as the new governor at a formal event where a chunky ceremonial chain was placed around his neck, as Maňka and top city officials looked on, shell-shocked.

During his first year in office, Kotleba employed dozens of his party members in jobs at the local administration. Green-shirted security guards blocked the doors, giving the place the air of a cult headquarters. One of his first moves was to remove the EU flag from the administration building, in line with his belief that Slovakia should withdraw from both the EU and Nato.

Kotleba did not have control of the regional parliament, which tried to frustrate his initiatives at every turn, but he set about making his influence felt wherever he could. He was particularly put out by programmes promoting human rights and tolerance in schools, and issued guidelines suggesting that instead of doing that, it would be better if the schools held beauty pageants. These were aimed at “girls learning to present themselves as ladies, and for them to see that there is still a world that values women’s dignity and spiritual beauty”. Some schools ignored the recommendations and still held the anti-extremism sessions; others did indeed hold beauty contests. Kotleba’s Kulturkampf continued in other areas, as he cancelled a contemporary dance festival he deemed to contain “pornography”, as well as an EU-funded project to resettle people with mental disabilities from a decaying communist-era facility into smaller supported housing units, and reintegrate them into society.

When the time came to campaign across the nation for the 2016 parliamentary elections, Kotleba and his party made good use of the deft double messaging common to extremists trying to go mainstream: putting on a more humane face for the general public, while providing clear signals for the core support. He attended an extreme-right march in Bratislava, where he wished everyone present “a happy White day”, to raucous applause. The party handed out charitable donations to youth sports clubs and other approved causes, but the amount on several occasions was €1,488, a number widely used as code by neo-Nazis. (The number 14 refers to the Fourteen Words, a white supremacist slogan, while 88 stands for Heil Hitler, as H is the eighth letter of the alphabet.) Uhrík told me it was merely a coincidence.

In interviews, Kotleba claimed to be outraged at accusations of racism, and said he was simply defending the “decent people”, who were now endangered by a new threat: the large numbers of migrants and refugees arriving in Europe from Africa and the Middle East. All the previous rhetoric about the Roma could now be grafted on to a new and even more threatening “enemy”. He was largely shunned by state television, but was active on Facebook and other social media, and stepped up his leafleting by mail. The leader, with an entourage of green-shirted disciples, travelled to the forgotten towns and villages once again, promising to restore dignity to the forgotten peoples of Slovakia, stripped from them so cruelly by the corrupted, decadent Slovak elites.

As the parliamentary vote approached, the political rhetoric across the spectrum shifted closer towards Kotleba. Politicians across central Europe said they did not wish to support migrants when there were still so many people living in poverty in their home countries, and Slovakia was no exception. “Islam has no place in Slovakia,” said prime minister Fico, nailing his colours to the rightwing, anti-refugee mast. Two Slovak researchers, Viera Žúborová and Ingrid Borárosová, concluded that the endless mainstream discussion of the migration topic “logically had to bring advantages for the party which had been for years presenting itself with Eurosceptic politics and hostility against minorities”. While it’s possible that Smer wooed some of Kotleba’s voters by claiming the migration issue as their own, adopting the same kind of inflammatory language perhaps signalled to others that Kotleba had been right all along. His party won 8% of the vote and ended up with 14 seats in parliament.

In Bratislava, the result sent shockwaves through polite society. Previously, it had been possible to dismiss Kotleba as a freakshow in the provinces; now he was at the heart of national politics. There was a hand-wringing discussion about how to treat the country’s newest parliamentarians – reminiscent of debates happening elsewhere as parties formerly considered fringe extremists began taking government offices. Andrej Kiska, who occupied the largely symbolic presidential role, was the one liberal force in Slovak politics, and refused to invite Kotleba to the presidential palace as is customary with heads of new parliamentary parties. “Let’s draw a clear line: these people are fascists and we won’t cooperate or talk with them,” he told Slovaks, explaining his decision.

At the liberal newspaper Denník N in Bratislava, editorial staff held discussions to decide how to cover Slovakia’s newest political force. “All of us know that he’s a fascist who is pretending to be a guy wearing a suit,” editor-in-chief Matúš Kostolný told me. He felt the paper should cover the actions of Kotleba’s MPs, but not carry interviews with them or treat them like regular parliamentarians. “I did a lot of research about how this was handled in other countries, and basically there are no good solutions. If he were in power, he’d be attacking the system we live in, so why should public television discuss his toxic ideas?”

Others weren’t so sure. The veteran war correspondent Andrej Bán argued that while Kotleba himself should be blacklisted, it was worth engaging with party members. Bán thought it was necessary to listen to Kotleba’s supporters, and later set up an organisation called Forgotten Slovakia, which organised public discussions in small towns across the country.

Polling showed that some of the most radical Kotleba fans were young Slovaks, most of whom consumed their news via Facebook. Among 18- to 21-year-olds, Kotleba’s party had got more votes than any other at the 2016 parliamentary elections. In one region, schools organised mock elections among students, and Kotleba won every time. “They poison the well of young people. If you start at age 11, then by 16 you can have a brainwashed Nazi. Without Facebook, Kotleba wouldn’t be in parliament,” claimed Vašecka, the sociologist.

A number of NGOs began organising discussion groups in schools to try to increase political engagement among young people. Michal Dzurko, Kotleba’s former student, had flirted with extremism but later became a committed campaigner against it. He travelled to schools to hold discussion sessions with radical young pupils. The children asked many questions, and often he could see that there were new thought processes whirring in some of their heads. “Nobody had taught them the basics of how to be a citizen,” he said. “They can tell you all the parts of a fucking maple leaf in Latin because that’s what they teach in school, but nobody teaches them media literacy or how the world works.”

Soon, it was time to think about who would stand against Kotleba in the November 2017 regional elections, in which he wanted to secure another four-year term as Banská Bystrica governor. Ján Lunter, a wealthy local businessman, was keen to run, and thought the best way to beat Kotleba was to offer a positive agenda, rather than to focus on the evils of Kotleba’s ideology and try to shame people into not voting for an extremist. Born into a farming family but a longstanding vegetarian, Lunter had begun producing tofu in the early 1990s, back when vegetarian foods were hard to come by. By 2017, the company was producing seven tonnes of tofu per day, selling it across central Europe, and employed 200 people at its factory just outside Banská Bystrica. With a creased face and boomerang eyebrows, he looked slightly dishevelled in a suit, giving him simultaneous airs of respectability and relatability. He was by no means a charismatic orator, but he was possessed of a Zen-like calm that he would maintain all through the electoral campaign. Importantly, he was not a career politician, and had no links to Smer or other established political forces. The main political parties, and most other interested independents, stepped back to give Lunter the best chance of winning.

Lunter’s son Ondrej, who ran his father’s campaign, engaged a set of Bratislava consultants to help craft the messaging, led by Peter Hajdin, a youthful 45-year-old with a fortnight’s worth of beard. Hajdin had worked on President Kiska’s campaign in 2014, helping him to a surprise victory against Fico, the Smer prime minister who had been keen to transfer to the presidential palace. For Lunter, Hajdin thought of a fairly straight campaign that would promote him as a decent, honest, hard-working businessman. The words Kotleba, Nazi, extremism or anything similar were not to be used. It was better to communicate with people by showing them a different vision of politics, he thought, rather than by yelling at them. The care and energy put into the campaign was in stark contrast to Maňka’s run four years earlier. Hajdin created slick branding, starting with the logo – a white, all-caps LUNTER in a chunky, no-nonsense font, embossed on a red rectangle. “I wanted something like a Swiss chocolate logo, something tasty you’d like to have a bite of,” he told me in the offices of his Bratislava agency. Three campaign teams toured the region with balloons, leaflets and big smiles.

In Bzovík, a typical town of around 1,000 residents an hour’s drive from Banská Bystrica, Kotleba had won comfortably in 2013. Michaela Urban, a community organiser who helped organise campaigning for Lunter in 2017, admitted that she herself had voted for Kotleba in 2013. “I knew absolutely nothing about him – it was just about voting against Maňka. I don’t think many people knew that much about him then.” In the four years of his governorship, Kotleba came to the town frequently, she said, to check on the progress of restorations to the 17th-century castle. He also repaired a road to the village that had been bothering locals for years. “A few people like the ideology, but most people like him because it seems he takes an interest,” she said.

Nevertheless, it seemed likely that many people did also approve of aspects of Kotleba’s rhetoric. “Everywhere I went, people asked me what I would do about the Gypsies, and said at least Kotleba did something,” Lunter told me, about his campaign visits around the region. Like many Slovak towns, Bzovík had a completely segregated Roma community, who lived in a settlement down a muddy track on the outskirts, where houses were stacked together higgledy-piggledy, unlike the neat bungalows in the rest of the town. Ownership rights were murky, even though the community has been there for generations. “Animals are more protected in this country than Roma people,” 47-year-old Eva Grešková complained to me, as she cooked lunch inside one of the houses. Tensions had increased over the years of the Kotleba governorship, she said, as the governor’s rhetoric removed any vestigial taboo around open discrimination against Roma. She had a litany of unpleasant cases, from muttered abuse on the street to bus drivers refusing to take Roma kids on board.

As the vote approached, Banská Bystrica was on edge. A dance theatre to which Kotleba had cut funding rehearsed a new show about the battle between good and evil, to premiere shortly after the election. They created posters featuring a man trying to jump over a ravine, with a demonic green hand emerging from the depths to pull him in. The posters read “Good/Evil Prevails”. The theatre rehearsed two alternate endings, to be used depending on the electoral result.

On election night, everyone awaited the votes from the countryside nervously, remembering what had happened four years ago. In a number of small towns and villages like Bzovík, Kotleba won a majority again, but by midnight it was clear that Lunter would easily win the overall vote, and the celebrations began in the restaurant the Lunter team had hired. By the time Lunter and his small entourage arrived at the governor’s office to take up their new jobs a few weeks later, almost everything had been stripped from the walls and cabinets, but there were a few curious discoveries. In a side-room off the governor’s office they found a camp bed. Kotleba, apparently, had been sleeping there. In a cabinet, they found three different drafts of a grovelling letter to the Russian ambassador apparently written by Kotleba, in which he said he wanted to buy a Russian car and hoped for any assistance possible from Russia. When I met Lunter, he retrieved the drafts from a grey folder marked “Kotleba” that he still keeps in his office, and read one out with a smirk. It was not clear if any version of the letter was ever sent, but it appeared to bolster rumours of illicit funding from Moscow, which Uhrík strongly denied to me.

In the days after the vote, dancers from the theatre went around town with a red marker and crossed out the “evil” on their posters, so that they now read simply, “Good prevails”. After four years, Banská Bystrica had finally got rid of Kotleba. Lunter, asked what his first act as governor would be, said he planned to open the windows of the regional administration building and let in some fresh air.

Back in 2013, Kotleba had benefited from a perfect storm of hometown factors – complacent incumbent, widespread disillusion, low voter turnout, and slick online and in-person campaigning – to win victory. The years of Roma isolation and alienation also helped, with Kotleba’s unpleasant rhetoric finding a receptive audience among many frustrated rural residents. With a well thought-out campaign, Lunter was able to beat him easily, despite not being a particularly charismatic politician. Although he is now an established fixture in Slovak politics, Kotleba is ultimately seen as too much of a genuine extremist to win real majorities nationally. Ahead of March’s presidential elections, most polling has him unlikely to break double figures.

It would be nice to think that, after four years of Kotleba, the people of Banská Bystrica had an epiphany and realised he was a charlatan and a racist. But Kotleba all along was a symptom, not a diagnosis, and it’s hard to draw the conclusion that all is well with politics in Slovakia. Kotleba – whose current presidential campaign posters say “Family is a man and a woman: Stop LGBT” and “finally a Slovak president” – is often mentioned in a pairing with Boris Kollár, a flamboyant businessman whose party, We Are Family, also made it into parliament in 2016 on a vague “family values” programme. Kotleba attracted a large proportion of angry provincial men, while Kollár attracted large numbers of disillusioned women from the regions, according to Slovak pollsters.

When I met Kollár in his parliamentary office recently, he was dressed in a sharp suit and characteristically loud tie. “Voters don’t read election programmes, voters decide based on emotions,” he told me as he chomped on expensive chocolates. Kollár has 10 children from nine different women, yet says he named his party We Are Family because his focus was on “traditional conservative values when it comes to the family”. Was it some kind of joke, I asked. “I have shown I can look after my children, it’s proof I can look after all the children,” he said, clarifying that his traditionalism was mainly focused on opposing the expansion of LGBT rights. When I asked what his solution to the issue of Roma poverty and isolation was, he looked at me very seriously, and said: “We’ll buy them 700,000 plane tickets and send them all to England and see how you like it.” He lifted his head back and gave a huge roar of laughter. Then he said: “That was a joke.” Kollár set up his party five months before the elections; he got nearly 7% of the vote and now has 11 MPs.

The response of prime minister Fico and his ruling Smer party to the rise of these populist and extremist parties was to try to stifle them by pilfering their playbook. Fico called journalists “dirty anti-Slovak prostitutes”, claimed anti-government protests were organised by George Soros, and continued the rhetoric against migrants and refugees. Protests against his government erupted last spring over the murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancee. They were shot dead at home, as Kuciak was investigating alleged ties between government-linked figures and organised crime, and the killings shocked the urban elite. The protesters who flooded the central squares in cities across the country were mainly middle-class, liberal Slovaks. I even met some government ministry employees at one protest in Bratislava last April. They said it was time for a different kind of politics, without corruption and ties to organised crime. The protesters had no party orientation, but protested under the slogan For a Decent Slovakia. To everyone’s surprise, Fico stepped aside in March last year, although Smer is still in government. A countrywide movement was formed, outside party politics, holding rallies and meetings under the Decent Slovakia brand, to keep up the pressure on the ruling elite.

It was that same word – decency – of which Kotleba was so fond. Indeed, some of the core demands of the Kotleba greenshirts were not so different to those of the middle-class protesters in Bratislava. Both wanted a crackdown on graft, new politicians who listened, and were demanding respect and decency.

President Kiska, the one prominent progressive politician in the country, is not standing for re-election next month, and while Kotleba is unlikely to win, progressive Slovaks are worried about Štefan Harabin, a former minister of justice known for colourful insults, disdain for the media and occasional nationalist rhetoric. The establishment, Smer-backed candidate is Maroš Šefčovič, a vice-president of the European Commission’s Energy Union, who has little experience of electoral politics. If Harabin gets to the second round and picks up the votes of Kotleba and other nationalists, he may have a shot at winning.

Before leaving Slovakia, I paid a visit to the presidential palace, a grand, gaudily renovated complex in central Bratislava, where I chatted with Rado Baťo, a political advisor to the president with a James Joyce quote tattooed on one arm and a sloth on the other. He said the focus groups his team had carried out showed a surprisingly large crossover between Kotleba voters and Kiska voters. Many of the same people who voted for a progressive liberal in favour of minority rights as president had backed a far-right extremist party in parliamentary elections. It suggested that actual policies mattered less than the perception of a willingness to shake up the system, he said. “Slovak politics is no longer divided between left and right. People don’t care if parties are leftwing or rightwing. They just want the government to get shit done.”

• This article was amended on 14 February 2019. An earlier version suggested Kotleba lost his governorship before taking his party into parliament, but it was after. It also referred to Štefan Harabin as a former high-court judge; he is a former minister of justice, but remains a judge; and Maroš Šefčovič is a vice-president at the European Commission, not a deputy commissioner.

Shaun Walker